Table of Contents

Zeliger’s Paradox: Infinite Regress of Causes

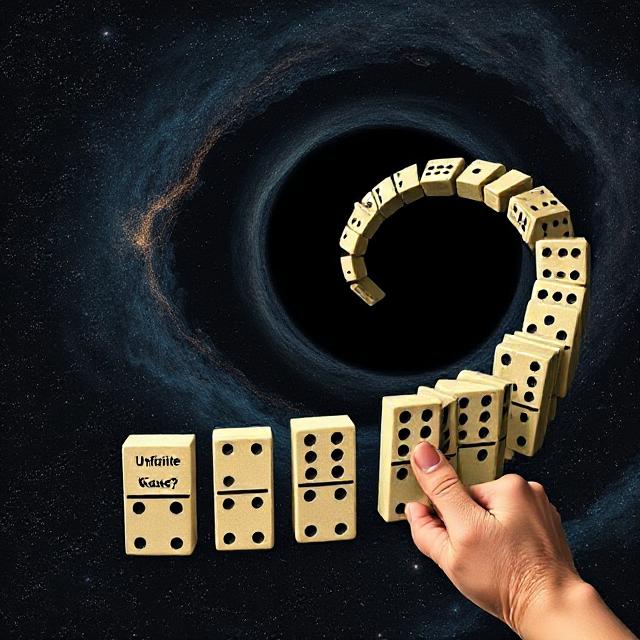

At the heart of every explanation lies a question: Why? Why did this event happen? Why does the universe exist? Why do we experience anything at all? In seeking answers, philosophers often stumble upon the elusive specter of infinite regress. One such haunting formulation is Zeliger’s Paradox, which confronts us with a dilemma: can a chain of explanations ever terminate, or must it stretch back endlessly?

Zeliger’s Paradox is not as famous as Zeno’s or the Grandfather Paradox, but it represents a profound metaphysical and epistemological challenge. It raises the question of whether any explanatory chain can be complete without a first, uncaused cause—or whether every answer leads to another question, ad infinitum.

I. Understanding Infinite Regress

An infinite regress occurs when a proposition depends on a previous one, which in turn depends on another, and so on, without any ultimate starting point. In philosophy, infinite regresses often arise in discussions of causality, knowledge, justification, and existence.

A. Examples of Infinite Regress

- Causal Regress: What caused the Big Bang? Then what caused that cause?

- Epistemic Regress: I believe X because of reason Y, but Y is justified by Z, and so on.

- Moral Regress: Why is stealing wrong? Because it harms others. Why is harm bad? Because…

Some infinite regresses are considered benign (e.g., in mathematics), while others are vicious, meaning they undermine the possibility of meaningful explanation. Zeliger’s Paradox belongs to the latter.

II. The Formulation of Zeliger’s Paradox

Zeliger’s Paradox arises from the observation that:

“Every explanation requires another explanation. If no explanation is self-contained, then nothing is ever fully explained.”

This leads to the conclusion:

- Either we accept an infinite regress of causes,

- Or we must assert a self-existent, uncaused cause.

Neither option seems satisfying.

A. Infinite Explanation Problem

If each answer demands another answer, knowledge itself becomes impossible to complete. How do we ever stop explaining?

B. Arbitrary Termination Problem

If we stop the chain arbitrarily—”this is just how it is”—we risk intellectual laziness. Why should one point in the chain get a free pass?

C. Self-Caused Entities?

Can anything explain itself? The idea of a self-caused entity or “necessary being” is controversial. How can something cause itself without already existing?

III. Historical Roots: Aristotle to Aquinas

Zeliger’s Paradox echoes ancient philosophical struggles with causality and explanation.

A. Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover

- Aristotle posited that there must be a first cause that itself is uncaused.

- The “unmoved mover” initiates motion without being moved.

B. Aquinas’ Cosmological Argument

- St. Thomas Aquinas expanded this idea in his Five Ways, arguing that a first cause is necessary to avoid infinite regress.

C. Hume and Kant: Skepticism of Causality

- David Hume challenged causality as a mental habit, not a real connection.

- Immanuel Kant questioned whether our reasoning about causation applies outside of human experience.

Zeliger’s Paradox reinvigorates these debates in modern analytic terms.

IV. Modern Responses and Theoretical Implications

A. Foundationalism

In epistemology, foundationalists argue that some beliefs or causes are basic, needing no justification.

- Example: “Cogito, ergo sum” as a foundational truth.

- In causality, this would equate to accepting a brute fact or necessary being.

B. Coherentism

Others argue that justification can be circular if the system is coherent as a whole.

- No “first cause” needed if the web of beliefs supports itself.

- This challenges the need for linear causality altogether.

C. Multiverse and Quantum Theory

- In speculative physics, some posit a self-sustaining multiverse or cyclical time.

- In these views, causality might loop or recycle, avoiding the need for a single origin.

V. Zeliger’s Paradox in the Real World

A. Scientific Explanation

Science often postpones ultimate questions:

- “We don’t know what caused the Big Bang yet.”

- But Zeliger’s Paradox asks if science can ever answer that, or if it’s asking too much.

B. Theological Implications

- The paradox bolsters arguments for a divine creator.

- Alternatively, it can be used to criticize theological claims that invoke a God as a “first cause” without adequate explanation.

C. AI and Recursive Design

- As AI systems become more autonomous, questions arise:

- Who programmed the programmer?

- Can an intelligence ever fully understand its own origins?

VI. Philosophical Reflections: Can Explanation End?

Can we truly live with an unending regress? Or is it more honest to admit we must terminate explanation arbitrarily at some point?

A. The Cost of Endless Why

- Imagine a child asking “Why?” to every answer. Eventually, we say, “Because.”

- Does that mean we fail in explanation, or accept the limits of human reason?

B. The Illusion of Completion

- Perhaps the desire for a final cause is psychological, not philosophical.

- Explanation may be a tool, not an endpoint.

VII. Thought Experiment: The Infinite Why

Imagine a machine that can answer any “why” question. You ask it:

- Why does the apple fall?

- Because of gravity.

- Why gravity?

- Because of spacetime curvature.

- Why curvature?

Eventually, the machine either loops or says, “There is no further answer.” Zeliger’s Paradox lives in that gap—the point where even explanation breaks down.

VIII. Conclusion: Zeliger’s Paradox and the Nature of Explanation

Zeliger’s Paradox is more than a logical quirk. It is a philosophical mirror showing the fragility of our deepest assumptions. Whether you favor infinite chains, brute facts, or self-contained systems, each choice reshapes your view of reason, reality, and understanding.

The question Zeliger’s Paradox leaves us with is not, “What is the first cause?”—but rather, “Can we ever stop asking why?” And perhaps that’s the most human question of all.