Table of Contents

What Is Truth? Correspondence vs Coherence Theories Explained

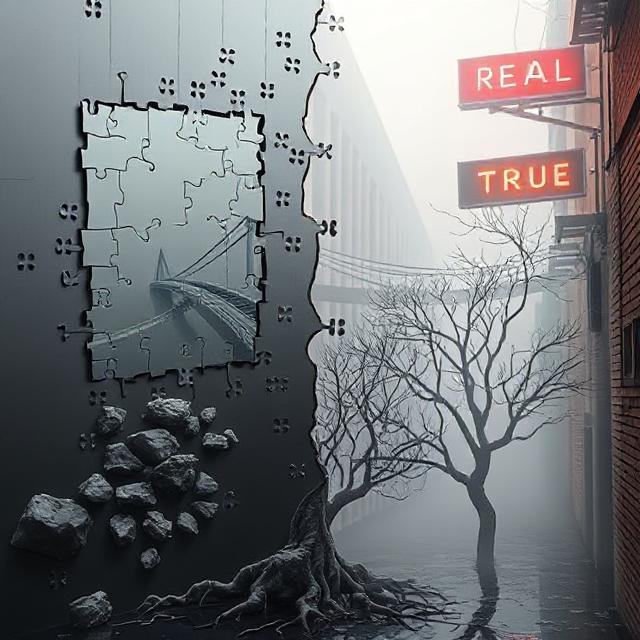

“What is truth?” This ancient question echoes across millennia of human thought. It has challenged philosophers from Plato to Nietzsche and remains as pressing today in the age of AI, misinformation, and hyperconnectivity. When we say something is “true,” what do we actually mean? Is truth a reflection of the world as it is, or is it something that fits neatly into a coherent system of beliefs?

Philosophers have long proposed various theories of truth, but two foundational frameworks stand out: the correspondence theory and the coherence theory. Understanding these models is not just an academic exercise—it shapes how we think, reason, and justify our beliefs.

I. The Correspondence Theory of Truth

The correspondence theory holds that a statement is true if it accurately reflects the way the world actually is. In short, truth corresponds to facts.

Origins and Proponents

This view traces back to Plato and Aristotle, who saw truth as a matter of stating what is, as it is. Aristotle famously said, “To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false; while to say of what is that it is, or of what is not that it is not, is true.”

Modern advocates include:

- Bertrand Russell: Argued that statements mirror external reality.

- G.E. Moore: Emphasized common-sense realism and factual alignment.

- Alfred Tarski: Formalized the idea with semantic precision: “‘Snow is white’ is true if and only if snow is white.”

Core Concepts

- Truth is objective: It exists independent of human perception.

- Truth is binary: A proposition is either true or false based on its match with reality.

- Truth relies on evidence: Observation and empirical data verify correspondence.

Examples

- “The Eiffel Tower is in Paris.” True because the actual tower is in Paris.

- “Water boils at 100°C at sea level.” True because it matches observed physical behavior.

Strengths

- Intuitive and aligns with science.

- Grounded in observable reality.

- Easy to apply in factual, empirical domains.

Weaknesses

- Difficult to apply to abstract concepts (e.g., justice, love).

- Raises questions about how we access reality (epistemological limits).

- Assumes language mirrors the world in a straightforward way.

II. The Coherence Theory of Truth

The coherence theory defines truth as the consistency and harmony of a statement within a larger system of beliefs. In this view, something is true if it “fits” well with what we already accept as true.

Origins and Proponents

This view gained traction with rationalist and idealist philosophers:

- Baruch Spinoza: Emphasized internal consistency over empirical grounding.

- Hegel: Saw truth as emerging from the unfolding dialectic of ideas.

- Brand Blanshard: A 20th-century defender who argued that truth must form a unified, logical whole.

Core Concepts

- Truth is systemic: It depends on how well beliefs fit together.

- Truth is contextual: Defined within the framework of a specific worldview.

- Truth evolves as systems of belief are refined.

Examples

- In mathematics: “The square root of 9 is 3” is true within the system of arithmetic.

- In ethics: “Slavery is immoral” fits with modern coherent systems of human rights and dignity.

Strengths

- Applies well to abstract and complex domains.

- Emphasizes logical integrity.

- Flexible and adaptive to new knowledge.

Weaknesses

- Truth becomes relative: Different coherent systems may conflict.

- Risk of circularity: A belief is true because it fits, but it fits because it’s believed.

- Less grounded in empirical verification.

III. Correspondence vs Coherence: A Comparative Lens

| Feature | Correspondence Theory | Coherence Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Truth | Matches external reality | Fits within belief system |

| Nature of Truth | Objective | Contextual, systemic |

| Use Case | Empirical, factual claims | Ethical, abstract reasoning |

| Verification | Observation, data | Logical consistency |

| Risk | Misperceiving reality | Circularity, relativism |

IV. Where the Theories Meet: Pragmatic Considerations

While these theories often seem at odds, many modern philosophers advocate for a pragmatic synthesis. The American philosopher William James proposed that truth must not only correspond and cohere but also “work” in real life. In the pragmatic theory of truth, the usefulness of a belief helps determine its truth.

In practice, we often blend theories:

- Scientists aim for correspondence with data, but also check that their findings cohere with accepted theories.

- Ethical and legal systems depend on coherence, yet seek correspondence with human rights outcomes.

This flexible approach reflects how truth is pursued across disciplines.

V. What Is Truth in the Digital Age?

In an age of deepfakes, misinformation, and algorithmic manipulation, the question “what is truth” takes on new urgency.

- Correspondence: How can we verify facts in a sea of information?

- Coherence: How do echo chambers create systems of belief that feel true but are unmoored from reality?

Modern epistemology must account for:

- The limits of perception and bias.

- The role of authority and consensus.

- The need for media literacy and philosophical rigor.

Philosophy’s answer to “what is truth” must evolve with technology, but the core questions remain: What do we believe, why do we believe it, and how do we know it’s true?

VI. Conclusion: Why Truth Still Matters

So, what is truth? Is it a mirror reflecting the world, or a web of beliefs held together by internal harmony? The correspondence and coherence theories each offer powerful insights. One prioritizes factual accuracy; the other, logical integration.

Ultimately, the pursuit of truth demands both perspectives. We need correspondence to anchor us in the world and coherence to make sense of that world through reasoned thought. When combined with pragmatism, this triad can help us navigate the complexities of knowledge, belief, and understanding.

In a world where truth often feels contested or elusive, returning to philosophy’s foundational question is more vital than ever. Truth matters because it shapes action, builds trust, and forms the foundation of any meaningful discourse.