Table of Contents

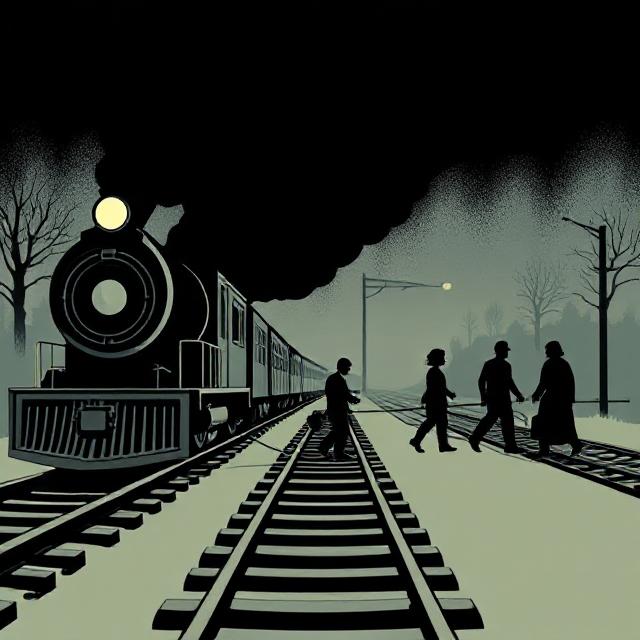

Introduction: What Is the Trolley Problem?

The Trolley Problem is a famous thought experiment in moral philosophy, originally introduced by Philippa Foot in 1967. At its core, it’s a question about whether it is morally acceptable to sacrifice one person to save many others—a scenario that highlights the tension between utilitarianism (maximizing outcomes) and deontology (following moral rules).

In its original form, a runaway trolley is heading toward five unsuspecting people tied to the tracks. You are standing near a lever. If you pull it, the trolley diverts onto another track, where it will kill only one person. Do you pull the lever?

This hypothetical puzzle, deceptively simple, has given rise to numerous variants, each amplifying the ethical stakes or adjusting the framing. These variations expose the fragile assumptions behind our moral intuitions and question whether our ethics are as consistent as we’d like to believe.

I. The Classic Trolley Problem

Scenario:

- Five people are on the main track.

- One person is on the side track.

- You are near a switch.

- Pulling the switch diverts the trolley.

Core Ethical Dilemma:

- Pull the lever? You save five but kill one.

- Do nothing? Five die, but you didn’t actively intervene.

Philosophical Tensions:

- Utilitarianism: Save the greatest number—pull the lever.

- Deontology: Do not kill intentionally, even for a good outcome—do nothing.

This basic setup pits outcome-based ethics against rule-based ethics, raising the question: Is actively causing harm worse than passively allowing greater harm?

II. The Fat Man Variant (Push Version)

Judith Jarvis Thomson extended the original problem by making it more emotionally and physically direct.

Scenario:

- A trolley is heading toward five people.

- You are on a footbridge with a large man.

- Pushing him will stop the trolley, killing him but saving the five.

Why It Changes Everything:

- Instead of pulling a lever, you now physically push a man to his death.

- The mechanics are similar: kill one to save five.

- But our moral intuition usually recoils. Why?

Analysis:

- Proximity and agency: Pushing feels more like murder than pulling a lever.

- Moral intuitions: We are less comfortable with hands-on killing.

- Doctrine of Double Effect: Pulling a lever feels like a side effect; pushing feels like a direct intention.

III. Loop Variant

Scenario:

- A trolley is heading toward five people.

- You can divert it onto a loop track where one man stands.

- His body will stop the trolley, saving the five.

Ethical Complication:

- The man’s death is instrumental—it’s the reason the five are saved.

- In the classic switch case, the death is a side-effect.

Insight:

- Intention matters. If the person’s death is the means of saving others, it may be judged morally worse.

- The utilitarian outcome is the same, but deontological analysis differs.

IV. Transplant Surgeon Variant

A thought experiment by Thomson that exaggerates the logic to absurdity.

Scenario:

- A surgeon has five patients needing different organs.

- A healthy man walks in for a check-up.

- Should the surgeon kill the healthy man to harvest his organs and save five?

Intuition vs. Logic:

- Most people say “no,” but why?

- Utilitarian logic still suggests yes.

- But it violates moral rules, trust, and societal norms.

This variant pushes the limits of instrumental reasoning—can a person ever be treated purely as a means?

V. AI and Autonomous Vehicles Variant

Scenario:

- A self-driving car must choose between swerving into one pedestrian or continuing on course into five.

Real-World Relevance:

- These aren’t hypotheticals anymore.

- Autonomous AI systems must be programmed with moral algorithms.

- Who gets to decide the value of human life?

Questions Raised:

- Should the car protect its passenger at all costs?

- Should it minimize total harm?

- Can morality be coded into machines?

VI. Child on the Tracks Variant

Scenario:

- You must choose whether to save five elderly people or a child.

- Or vice versa: five children vs. one older adult.

Variables:

- Age

- Potential life years

- Social role

- Emotional value

Philosophical Implications:

- Is it ethical to weigh lives by their potential?

- Are all human lives equal in moral worth?

- How do emotions skew rational analysis?

VII. Organ Harvest Lottery Variant

Proposed by John Harris in the form of a moral satire.

Scenario:

- A society randomly selects healthy individuals to be killed for organ harvesting to save others.

Lesson:

- Taken to extremes, utilitarian logic may erode moral and social structures.

- There must be constraints on optimization.

VIII. The Lazy Rescue Variant

Scenario:

- You can save five people easily, but you’re feeling lazy.

- You choose not to act because you don’t want to be bothered.

Key Insight:

- Omissions can be morally significant.

- Negligence, though passive, may be ethically damning.

This reminds us that inaction is not neutral. Ethics includes responsibilities—not just prohibitions.

IX. Real-World Applications and Moral Engineering

Medicine:

- Triage systems often follow utilitarian principles: treat who can be saved, not necessarily who is most deserving.

Military Ethics:

- Targeted strikes or drone operations wrestle with collateral damage vs. mission success.

Climate Policy:

- Present sacrifice to avoid long-term harm—a real-life moral trolley.

X. Moral Psychology Behind the Variants

Emotional Brain vs. Rational Brain:

- Studies show our amygdala lights up during personal moral decisions (e.g., pushing the man).

- Prefrontal cortex engages during impersonal scenarios (e.g., pulling a lever).

Cultural Factors:

- Some cultures are more collectivist, favoring utilitarian choices.

- Others emphasize individual rights and rules.

Moral Fatigue:

- Too many dilemmas cause people to shut down morally.

- Ethical decision-making has limits of endurance.

XI. Philosophical Theories at Play

| Ethical Theory | View on Trolley Problem |

|---|---|

| Utilitarianism | Always choose the outcome with the most lives saved. |

| Deontology | Actions must respect rights; don’t use people as means. |

| Virtue Ethics | Focus on the moral character of the agent. |

| Care Ethics | Emphasizes relationships and emotional context. |

| Moral Particularism | Context matters; no one rule applies to all cases. |

XII. Final Reflection: What Would You Do?

The Trolley Problem and its variants are not just academic riddles—they challenge how we think about life, responsibility, and the cost of action or inaction.

Every twist reveals something more about our ethical instincts:

- We recoil at direct harm, even if it saves lives.

- We rationalize indirect consequences more easily.

- We are deeply influenced by proximity, agency, and emotional resonance.

In a world increasingly shaped by technology and systemic dilemmas—from AI ethics to pandemic triage—the trolley problem is no longer just a thought experiment. It’s a mirror reflecting the deep contradictions and hidden premises of our moral reasoning.