Table of Contents

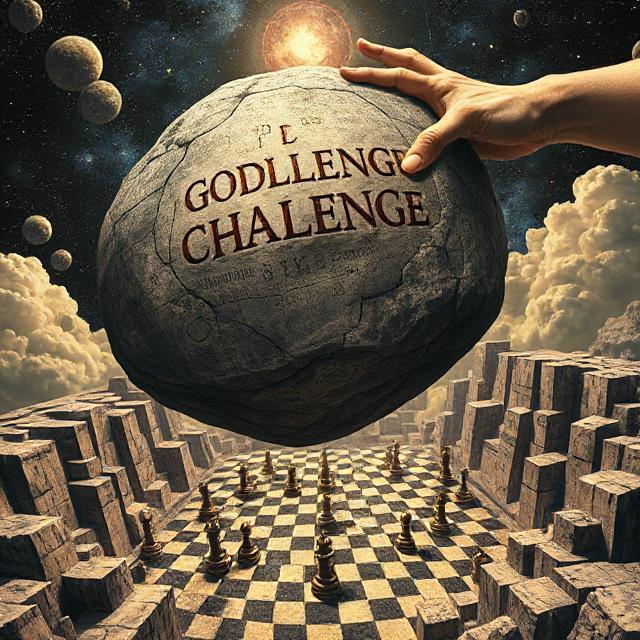

Paradox of Omnipotence: Can God Create a Rock He Can’t Lift?

The Paradox of Omnipotence is one of the most enduring and fascinating questions in theology and philosophy. It asks a simple but explosive question:

“Can an all-powerful God create a rock so heavy that even He cannot lift it?”

This question seems to put divine omnipotence in a bind: If God can create such a rock, then He cannot lift it—limiting His power. If He cannot create it, that too is a limitation. Either way, omnipotence appears logically impossible. Is this a genuine contradiction, or merely a linguistic trap?

In this article, we’ll unpack the paradox, explore its implications, and evaluate key philosophical responses from historical and contemporary thinkers.

I. The Problem Defined: Can Omnipotence Be Self-Limiting?

The paradox creates a self-referential loop:

- If God is all-powerful, He must be able to create anything, including a rock too heavy for Himself.

- But then He would be unable to lift it, thus not all-powerful.

This resembles classic logical paradoxes like:

- The Liar Paradox: “This statement is false.”

- Russell’s Paradox: A set of all sets that do not contain themselves.

In both cases, contradictions arise from self-referential logic.

II. Classical Theological View: Power Must Be Coherent

Many classical theologians, including Thomas Aquinas, argued that omnipotence does not include the power to do the logically impossible.

“It is not possible for God to make contradictions true.”

In this view:

- God cannot make square circles or married bachelors.

- Logical contradictions are not things but nonsense phrases.

Therefore, creating a rock He cannot lift is not a real task—it is nonsensical, like asking, “Can God make 2+2=5?”

Aquinas’ defense preserves omnipotence by limiting it to coherent possibilities.

III. The Modern View: Redefining Omnipotence

Some modern philosophers redefine omnipotence not as the ability to do anything whatsoever, but as the ability to do anything logically possible.

This avoids the paradox entirely by clarifying definitions.

Redefined Omnipotence: The ability to do all things that can logically be done.

By this standard:

- Creating an unliftable rock isn’t a real task.

- It’s a category error, mixing theology with incoherent propositions.

This approach is favored by analytic philosophers who prefer clean definitions over speculative metaphysics.

IV. The Logical Formulation of the Paradox

Let’s formalize the paradox:

Let P = “God is omnipotent.” Let R = “God can create a rock He cannot lift.”

If God can create R, then there exists something God cannot do (lift R). If God cannot create R, there is still something He cannot do (create R).

Thus, P implies not-P, which is a contradiction.

Resolution attempts must either:

- Reject P (limit God’s power), or

- Reject R as nonsense (say it has no truth value), or

- Revise the definition of omnipotence.

V. Atheistic Argument: The Paradox as Disproof

Some atheists use this paradox as an argument against the concept of God:

- If omnipotence leads to contradiction, then God is logically impossible.

- The very idea of an all-powerful being is self-defeating.

Critics respond that this is a straw man:

- It attacks a caricature of God rather than the refined philosophical concept.

- Just as we don’t ask if triangles can have five sides, we shouldn’t expect God to do the logically absurd.

VI. Paradox Variants in Other Traditions

A. Islamic Theology (Kalam)

Some scholars within Islamic theology accept a more absolute omnipotence, even over logic. God is not bound by rational rules.

However, others adopt a more Mu’tazilite view, aligning with reason and coherence.

B. Eastern Philosophy

Eastern traditions like Hinduism and Buddhism often see divine power as beyond human categories of logic entirely. The paradox would be viewed as irrelevant rather than troubling.

VII. Philosophical Analogies

A. Programmer Analogy

Imagine God as a programmer designing a universe. Could He write code that disables His own admin rights?

In software, yes—but doing so isn’t a contradiction unless we assume the admin must retain all powers at all times.

B. Storyteller Analogy

God as an author: Can an author write a character that defeats the author?

Yes in fiction, but it doesn’t limit the author’s real power—just explores it within a self-created world.

These analogies suggest that contextual power (within a world) may differ from absolute power (over all logic).

VIII. Theological Counter-Examples

A. Jesus and Divine Limitation

In Christianity, Jesus is seen as God incarnate, who chose to limit Himself.

- Hunger

- Sleep

- Death

This suggests voluntary limitation is compatible with divine omnipotence. The unliftable rock may be a metaphor for divine humility, not logical contradiction.

IX. Lessons from the Paradox

- Words have limits. Not all grammatically correct sentences are meaningful.

- Omnipotence must be coherent. Otherwise, it collapses into absurdity.

- Paradoxes provoke clarity. The value lies in the discussion, not the confusion.

- Faith and reason can co-exist. Reasonable definitions help faith remain intellectually robust.

X. Conclusion: Not All Power Is All-Possible

The Paradox of Omnipotence reveals that raw power, without coherence, leads to contradiction. By refining our definitions, we preserve the majesty of omnipotence without making it nonsensical.

Rather than disproving God, the paradox shows how language can deceive us. A being who is truly omnipotent would not be bound to perform absurdities, but rather to act with purpose, logic, and coherence.

The paradox, then, is not a trap for God but a test for human reasoning.