Table of Contents

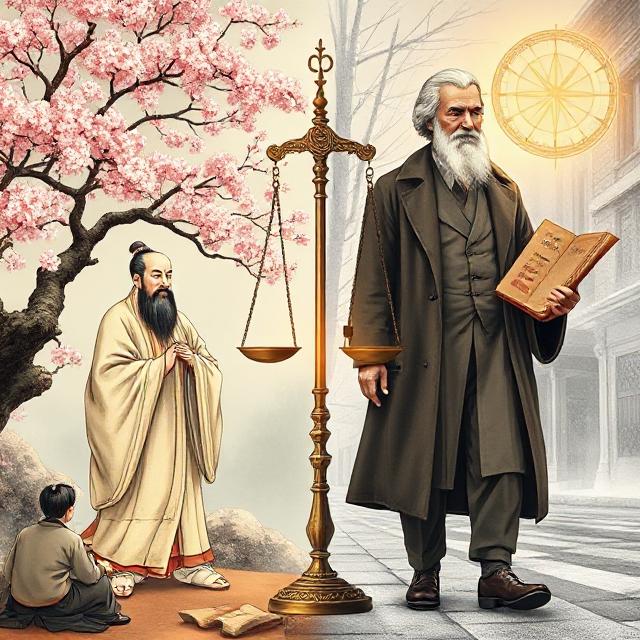

Moral Duty: Confucius vs Kant

Moral duty is a cornerstone of ethical thought across civilizations. Yet how it is understood differs vastly depending on cultural and philosophical contexts. This post explores two monumental ethical frameworks: Confucianism from the East and Immanuel Kant’s deontological ethics from the West. The focus keyword Moral duty: Confucius vs Kant reveals a striking contrast in how each philosopher conceptualizes what we owe to others, why we act, and what constitutes virtue.

I. Confucius: Duty as Harmony and Role Fulfillment

A. The Relational Foundation of Morality

In Confucianism, morality is rooted in relationships. Confucius (Kongzi, 551–479 BCE) envisioned a just society grounded in proper conduct within familial and social hierarchies. Rather than abstract principles, moral duty arises from one’s role:

- Child to parent (filial piety)

- Ruler to subject (benevolence)

- Elder to younger (guidance)

These roles are defined by li (ritual propriety) and ren (humaneness), guiding conduct through tradition and empathy.

B. Moral Duty as Contextual

Confucius taught that there is no one-size-fits-all rule. Duties depend on context, relationship, and the cultivation of virtue over time. This is ethics as an art:

“The superior man understands what is right; the inferior man understands what will sell.”

C. Education and Self-Cultivation

Confucian duty is not imposed externally but cultivated through lifelong learning, self-reflection, and social participation. Harmony emerges not from coercion, but from the internalization of moral sentiments:

- Learning poetry, music, and history develops sensibility

- Participating in rites builds communal identity

- Revering ancestors strengthens continuity

D. Limits and Critiques

Confucianism has been critiqued for reinforcing patriarchal and authoritarian structures. But it remains one of the most enduring systems of moral order, shaping East Asia’s approach to duty as relational harmony.

II. Kant: Duty as Rational Obligation

A. Reason as the Source of Moral Law

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) proposed a radically different view. In his deontological ethics, moral duty is universal, derived from pure reason. Duty is not about relationships or emotions, but the moral law:

“Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”

This is the Categorical Imperative: the test of whether an action can be willed consistently for all rational beings.

B. Autonomy and Moral Worth

Kant separates moral duty from outcomes. What matters is the intention guided by reason. A person has moral worth only when they act from duty, not from inclination:

- Giving out of sympathy is not truly moral

- Helping someone because it feels good lacks moral rigor

Duty is self-imposed by rational beings. To be moral is to legislate for oneself in the kingdom of ends.

C. The Universality of Ethics

Kant’s ethics are:

- Formal: not tied to specific relationships

- Atemporal: valid regardless of context or culture

- Egalitarian: every rational agent is equal under the moral law

He emphasizes respect for persons, never using someone as a mere means but always as an end.

D. Limits and Critiques

Kant has been critiqued for moral rigidity, lack of cultural nuance, and neglect of emotion. Critics argue that real-life ethics require flexibility, not only logic.

III. Comparative Table: Confucius vs Kant on Moral Duty

| Dimension | Confucius (Eastern) | Kant (Western) |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Duty | Relationships and roles | Rational will and universal laws |

| Core Concept | Harmony, propriety (li), humaneness (ren) | Categorical imperative, autonomy |

| Role of Emotion | Central to moral cultivation | Distrusted in moral motivation |

| Universality | Contextual and hierarchical | Universal and egalitarian |

| Moral Agent | Socially embedded individual | Autonomous rational self |

| Aim of Morality | Social harmony | Moral integrity and consistency |

IV. Integrating the Traditions

While seemingly opposed, the two approaches can be complementary:

- Confucian ethics teaches us the importance of relationships, respect, and context

- Kantian ethics offers clarity, consistency, and moral equality

In today’s multicultural societies, an integrated view can:

- Respect cultural traditions (Confucius)

- Uphold universal human rights (Kant)

- Promote both community and personal responsibility

V. Conclusion: Duty Between East and West

The comparison of moral duty: Confucius vs Kant reveals two profound visions of ethics:

- One rooted in ritual, role, and relationship

- The other in reason, rule, and universality

Rather than choosing one over the other, ethical maturity may involve balancing them. We must honor our specific bonds while also treating all people with equal respect.

In the end, both Confucius and Kant remind us that duty is not merely about action, but about the kind of person one becomes through those actions. A life of duty, rightly understood, is a life of character.