Table of Contents

Medieval Philosophy Theology: Bridging Faith and Reason

“Medieval philosophy theology”—three words that form a seamless triad when we look at the intellectual history of the Middle Ages. Unlike ancient philosophy, which was concerned with nature, logic, and virtue, medieval philosophy was steeped in theological questions. Why was this the case? Because philosophy in the Middle Ages was not a separate, secular endeavor—it was the handmaiden to theology, in a world where truth and divinity were nearly synonymous.

I. The Collapse of Classical Institutions

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, much of the classical intellectual tradition was lost or preserved only in fragments. Schools closed, urban centers declined, and the infrastructure for secular scholarship deteriorated. What remained strong, however, was the Church.

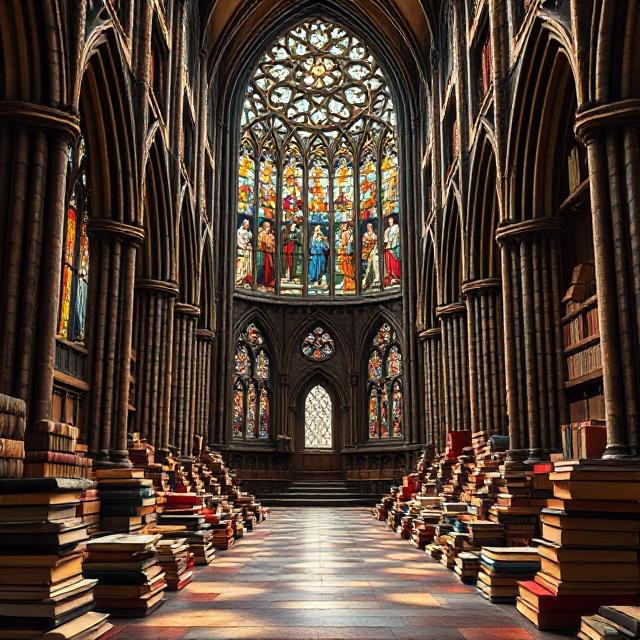

Monasteries and cathedral schools became the new custodians of knowledge. Philosophy survived primarily through Christian interpretation of classical texts, and the lens was overwhelmingly theological.

II. The Dominance of Christian Doctrine

By the early medieval period, Christianity was not only a religion but a total worldview. The Bible was seen as the highest form of truth, and all other knowledge had to conform to its teachings. Early thinkers like Augustine of Hippo believed that philosophy was valuable only insofar as it supported or clarified divine revelation.

Augustine famously wrote:

“Do not seek to understand in order to believe, but believe in order to understand.”

Thus, theology was not just a subject—it was the goal of intellectual inquiry. Philosophy became a tool for systematizing belief, exploring the nature of God, and defending doctrine.

III. The Influence of Islam and Judaism

While Christian Europe was grappling with theological unity, Islamic and Jewish philosophers were engaging deeply with Greek thought. Thinkers like Averroes (Ibn Rushd), Avicenna (Ibn Sina), and Maimonides were reinterpreting Aristotle through a religious lens.

Their works, translated into Latin in the 12th century, reintroduced Europe to Aristotle’s natural philosophy, metaphysics, and logic. However, even in this rediscovery, the motivation remained theological—how to reconcile reason with faith.

IV. Scholasticism: Reason Meets Revelation

Scholasticism was the dominant method of medieval philosophy—a rigorous, logic-driven approach to theology. It flourished in the universities of Paris, Oxford, and Bologna, and was led by figures like:

- Anselm of Canterbury – who gave the ontological argument for God’s existence

- Peter Abelard – known for Sic et Non, comparing contradictory theological authorities

- Thomas Aquinas – who synthesized Aristotle with Christian theology in Summa Theologiae

Scholastics used dialectic—the logical evaluation of opposing views—to clarify theological issues. Every argument about ethics, metaphysics, or nature began and ended with God as the ultimate ground of being.

V. Faith vs. Reason: A Productive Tension

The medieval period is sometimes caricatured as anti-reason, but this is misleading. Philosophers like Aquinas argued that faith and reason could not ultimately conflict because both came from God.

This belief created a productive tension:

- Faith provided foundational truths (e.g., Trinity, Incarnation)

- Reason clarified and defended them (e.g., proofs of God’s existence)

Even skeptical voices like William of Ockham, who emphasized divine omnipotence over rational deduction, worked within a deeply theological framework.

VI. Theological Topics of Medieval Philosophy

Because theology shaped the intellectual agenda, key philosophical questions revolved around:

- The existence and attributes of God

- The problem of evil and divine justice

- The nature of the soul and afterlife

- Free will versus predestination

- The metaphysics of sacraments

The question was never “Does God exist?” but rather “What is God’s nature?” or “How does divine grace operate in a rational universe?”

VII. Impact on Ethics and Politics

Even in domains like ethics or political theory, theological assumptions prevailed. For example:

- Ethics was based on divine law, not autonomous human reason.

- The state was viewed as a natural order permitted by God.

- Virtue was understood through the theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity.

Thinkers like Augustine, Aquinas, and Dante envisioned human life as a pilgrimage toward eternal union with God. Everything else—politics, law, education—served this ultimate telos.

VIII. Dissenters and Heresies

Not all philosophical voices fit neatly into orthodoxy. Thinkers like John Scotus Eriugena introduced Neoplatonic mysticism. Meister Eckhart taught a radical inwardness that bordered on pantheism. And some heterodox figures—like the Cathars or the Brethren of the Free Spirit—were condemned for veering too far from theological norms.

These movements show that even theological dominance left room for diversity and conflict, though always within the orbit of religious debate.

IX. The Gradual Secular Shift

By the late Middle Ages, tensions between theology and reason deepened. The rediscovery of classical texts, the rise of nominalism, and increasing focus on empirical methods began to erode the theological monopoly.

Figures like Marsilius of Padua began advocating for the independence of politics from Church control. This paved the way for Renaissance humanism, where man—not God—returned to the center of philosophical inquiry.

Yet, the legacy of medieval theology lived on, forming the groundwork for early modern philosophy, science, and even secular ethics.

X. Conclusion: A Philosophy Anchored in the Divine

Medieval philosophy theology was not a contradiction—it was a synthesis. Philosophy did not stand apart from theology; it served it. But it also sharpened it, stretched it, and questioned it.

In monasteries, cathedrals, and universities, thinkers asked the biggest questions imaginable—but always in the shadow of God. In doing so, they preserved and transformed the philosophical tradition, passing on tools of logic, metaphysics, and ethics that still shape our world today.