Table of Contents

Laozi’s Naturalness vs Aristotle’s Virtue: Two Visions of the Good Life

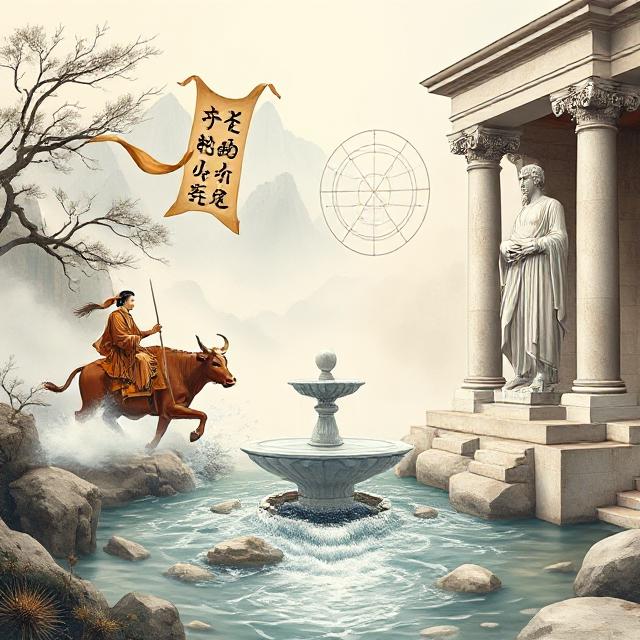

The comparison of Laozi’s naturalness vs Aristotle’s virtue reveals a profound tension in human philosophy: should we strive to cultivate our character through discipline and reason, or should we let go, returning to a more effortless alignment with nature? These two iconic figures represent opposite poles of ethical and metaphysical thought, each offering a unique vision of what it means to live well.

I. Laozi and the Dao: The Power of Naturalness

A. The Dao: Source of All

Laozi, the semi-legendary founder of Daoism, authored the Dao De Jing (“Way and Virtue Classic”). His central teaching is the Dao (Way)—the source of all existence, beyond language, logic, or categorization. The Dao flows effortlessly, like water, and those who live wisely harmonize with it.

B. Wu Wei: Action Without Force

A cornerstone of Laozi’s thought is wu wei, often translated as “non-action” or “effortless action.” It does not mean passivity, but rather a kind of spontaneous responsiveness:

“The sage does nothing, yet nothing is left undone.”

In this way of life, imposing structure, ambition, or artificial rules leads to disharmony. The highest moral being, then, is one who is natural, like an uncarved block, who does not interfere but flows with the Tao.

C. Moral Implication: Simplicity Over Effort

For Laozi, virtue is not something cultivated through struggle or training. Rather, it emerges when the self is emptied, desires are quieted, and the heart becomes still. Ethical living means:

- Avoiding extremes

- Yielding rather than conquering

- Simplicity, humility, and contentment

This path rejects rigid moral systems or codes in favor of inner attunement.

II. Aristotle and Virtue: The Art of Character

A. Eudaimonia: The Flourishing Life

Aristotle, writing centuries later in ancient Greece, proposed an entirely different view in his Nicomachean Ethics. For him, the highest human good is eudaimonia (flourishing or well-being), achieved through the exercise of reason and the development of moral character.

B. Virtue as Habit

Unlike Laozi, Aristotle saw virtue (αρετή, arete) as a skill or habit cultivated over time. Through practice, reflection, and guidance, individuals learn to:

- Act with courage

- Tell the truth

- Moderate desire

- Seek justice

Virtue is a mean between extremes (the Doctrine of the Mean). For example, courage lies between cowardice and recklessness.

C. Moral Implication: Training and Discipline

To live well is not to flow with the universe, but to train the soul through education and effort. Moral development requires:

- Ethical reasoning

- Self-mastery

- Social engagement and political responsibility

III. Comparing the Two Frameworks

| Aspect | Laozi’s Naturalness | Aristotle’s Virtue |

|---|---|---|

| Ultimate Goal | Harmony with the Dao | Flourishing through reason and virtue |

| Approach to Ethics | Letting go of effort and judgment | Deliberate cultivation of moral habits |

| Role of Reason | Distrusts intellectualization | Central to moral development |

| View of Self | Illusory, best when emptied | Rational, developing through effort |

| Social Role | Minimal interference, simplicity | Fulfillment through active participation |

IV. Strengths and Critiques

A. Laozi’s Strengths

- Environmental Wisdom: A worldview attuned to nature’s cycles

- Psychological Balance: Emphasizes contentment and humility

- Spiritual Depth: Offers peace in the face of chaos and suffering

Critique: May encourage passivity, political withdrawal, and neglect of justice.

B. Aristotle’s Strengths

- Practical Ethics: Useful in education, leadership, and civic life

- Human Potential: Sees greatness as something to be earned

- Social Vision: Champions human dignity and the importance of community

Critique: Can become rigid, elitist, and overlook the value of surrender.

V. Modern Resonances

A. Mindfulness and Naturalness

Modern spiritual seekers often embrace Laozi’s ideas through:

- Minimalism

- Taoist-inspired mindfulness

- Letting go of control

His wisdom aligns with Eastern meditation, Zen simplicity, and the rejection of over-engineered life.

B. Self-Development and Virtue

Self-help and education often mirror Aristotle’s ethics:

- Self-improvement programs

- Moral education and parenting

- Professional codes of conduct

The Western ideal of success through effort traces back to Aristotle’s emphasis on discipline and excellence.

VI. Toward Integration

Can these paths be reconciled? Some thinkers suggest a dialectic:

- Use Aristotle’s ethics for the outer world: responsibility, civic life, and relationships

- Apply Laozi’s naturalness for the inner world: stillness, release, and humility

A balanced life may involve alternating between cultivation and surrender, striving and flowing.

Conclusion: The Dao or the Discipline?

The contrast of Laozi’s naturalness vs Aristotle’s virtue presents more than a cultural divide—it reveals two eternal human impulses: to let go, or to take charge. One says: live simply and trust the flow. The other says: strive nobly, for virtue must be earned.

Neither path is complete alone. But together, they offer a compass for those who seek a meaningful life: walk the Way with awareness, and build your character with care.