Table of Contents

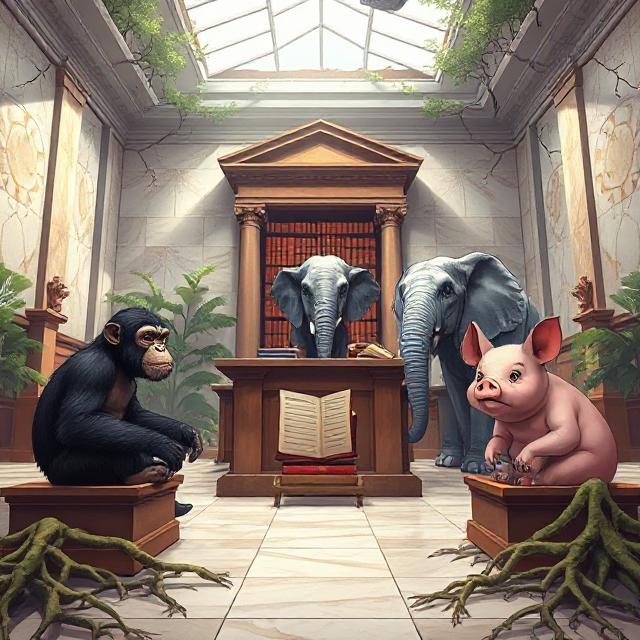

Animal Rights: Should Animals Be Moral Subjects?

Animal rights is one of the most urgent and transformative ethical conversations of our time. For centuries, animals have been used for food, labor, clothing, entertainment, and experimentation—all under the assumption that they exist for human benefit. But as science reveals the complexity of animal minds and philosophy expands the boundaries of moral concern, a profound question arises: Should animals be considered moral subjects?

To treat animals as moral subjects means recognizing that their experiences, interests, and lives carry moral significance. This article explores the historical foundations, philosophical arguments, and practical implications of animal rights. Should animals have rights similar to humans, or is it enough to ensure they are treated “humanely”?

I. What Does It Mean to Be a Moral Subject?

In ethical philosophy, a moral subject is any being whose interests should be taken into account in moral reasoning. Unlike moral agents, who can make ethical decisions (typically humans), moral subjects are beings who deserve moral consideration even if they lack agency.

This distinction allows us to include animals in the moral community, despite their inability to engage in abstract reasoning or moral debate. A dog cannot vote, but its suffering still matters. The concept of moral subjecthood makes it possible to argue that animals, like infants or people with severe cognitive impairments, should be protected not because of what they can do, but because of what they can experience.

II. Historical Roots of Animal Ethics

While concern for animals stretches back thousands of years, systematic animal rights philosophy only emerged in the last few centuries:

- Pythagoras and his followers in ancient Greece advocated vegetarianism out of respect for the soul in all living beings.

- Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism have long traditions of ahimsa (non-violence) toward all sentient life.

- Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, famously wrote: “The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

Modern animal rights was galvanized in the 20th century by philosophers such as Peter Singer, whose 1975 book Animal Liberation popularized the term speciesism, and Tom Regan, who argued that animals have intrinsic value and are “subjects-of-a-life.”

III. Sentience: The Moral Threshold

At the heart of animal ethics is the concept of sentience—the capacity to experience pain, pleasure, fear, and joy. Sentience is the ethical gateway that grants beings moral standing.

Science has now confirmed sentience in a wide array of animals:

- Octopuses show problem-solving intelligence and curiosity.

- Crows use tools and recognize individual humans.

- Pigs can outperform dogs on certain cognitive tasks.

- Elephants mourn their dead and show signs of empathy.

If we accept that suffering is morally significant, then causing avoidable suffering to animals becomes an ethical wrong, regardless of species.

IV. Arguments for Animal Rights

A. Equal Consideration of Interests

Animal rights proponents argue that the capacity to suffer should be the only relevant criterion for moral consideration. Denying animals moral status simply because they are not human is arbitrary.

B. Moral Progress

Slavery, sexism, and other forms of discrimination were once considered normal. Expanding moral concern to animals is part of a broader evolution in ethics.

C. Intrinsic Value

Many animals have preferences, social bonds, and a sense of well-being. Recognizing their intrinsic value, rather than just their usefulness, aligns with ethical consistency.

D. Legal and Societal Precedent

Legal reforms are beginning to reflect changing views:

- New Zealand and India have granted legal personhood to certain animals and rivers.

- Germany and Switzerland enshrine animal dignity in their constitutions.

V. Counterarguments and Criticisms

A. Human Exceptionalism

Critics argue that humans have unique capacities—rationality, language, moral agency—that justify superior moral status. However, this view is increasingly challenged by research into animal cognition.

B. Practical Concerns

Some worry that animal rights would disrupt industries, traditions, and livelihoods. But defenders counter that morality often requires changing harmful norms.

C. Rights vs. Welfare

Not everyone agrees animals need “rights.” Some suggest strong animal welfare protections are sufficient, provided cruelty is avoided. Others argue this is inadequate because welfare laws still treat animals as property.

VI. Religious and Cultural Views

Most major religions encourage kindness to animals, though they differ in doctrine:

- Christianity: Dominion over animals is tempered by stewardship and compassion.

- Islam: Permits animal use but requires humane treatment.

- Hinduism and Jainism: Promote vegetarianism and non-violence.

- Buddhism: Emphasizes compassion and interconnectedness.

These perspectives can serve as bridges between tradition and animal ethics.

VII. Animals in Law and Policy

While most legal systems treat animals as property, change is happening:

- Spain and Austria recognize animals as sentient beings.

- The UK Animal Welfare Act (2006) requires proper care.

- The Nonhuman Rights Project fights for legal personhood for chimpanzees and elephants.

Legal recognition helps reinforce moral subjecthood and protects against abuse.

VIII. Implications for Daily Life

If animals are moral subjects, our everyday choices become moral decisions:

- Eating meat or dairy raises questions about suffering and necessity.

- Buying products tested on animals involves complicity in harm.

- Entertainment involving animals (e.g., circuses, zoos) must be re-evaluated.

Living ethically in light of animal rights doesn’t require perfection, but it does require awareness and intentionality.

IX. Philosophical Questions Moving Forward

- Do animals have interests that can be balanced against human needs?

- Can animals be represented in legal and political systems?

- Is there a moral difference between killing and letting die in animal ethics?

- Should we extend rights to all sentient beings, including future artificial intelligences?

These questions stretch the moral imagination and challenge longstanding hierarchies.

X. Conclusion: The Expanding Circle

Animal rights asks us to widen our circle of concern beyond species lines. Treating animals as moral subjects is not about erasing differences between species, but about acknowledging that the capacity to suffer creates a claim on our moral conscience.

Recognizing animal subjecthood could mark a new chapter in human moral development—one that values empathy, justice, and humility in our relationship with the nonhuman world.