Your cart is currently empty!

20th-Century Analytic vs. Continental Split Explained

Table of Contents

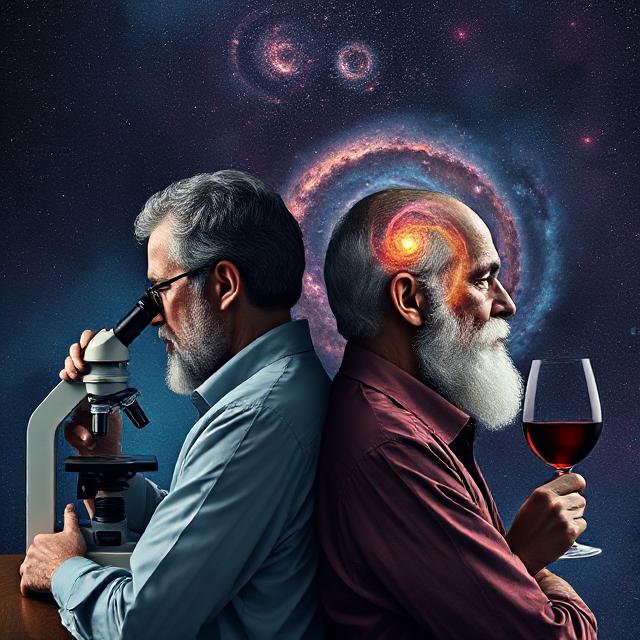

Analytic vs Continental Philosophy: The Great Divide of the 20th Century

The phrase “analytic vs continental philosophy” represents more than just a difference in intellectual style. It refers to a significant rift in 20th-century Western philosophy, one that cleaved academic departments, dictated journal acceptances, and defined entire careers. Each camp developed its own language, priorities, heroes, and methods. But how did this split happen? What do each side believe? And is this division still relevant today?

To understand the analytic vs continental philosophy divide, we must look at how each school of thought emerged, what questions they prioritized, and how their differing approaches to truth and meaning shaped modern academia.

I. Origins of the Divide: Post-Kantian Trajectories

The split has roots in post-Enlightenment thought, especially in how thinkers responded to Immanuel Kant. Two general trajectories emerged:

- Continental Philosophy evolved through German Idealism (Hegel, Schelling), phenomenology (Husserl, Heidegger), existentialism (Sartre, Camus), and post-structuralism (Foucault, Derrida).

- Analytic Philosophy took root in logical analysis, empiricism, and linguistic precision, influenced by Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein, and the Vienna Circle.

The term “continental” refers to Europe (particularly France and Germany), whereas “analytic” is primarily associated with English-speaking countries, especially the UK and the US.

II. Analytic Philosophy: Clarity, Logic, and Language

Analytic philosophy values logical clarity, argumentative rigor, and linguistic precision. The early analytic philosophers believed that many philosophical problems stemmed from misuse or misunderstanding of language.

Key Thinkers and Contributions:

- Gottlob Frege: Revolutionized logic and laid groundwork for linguistic analysis.

- Bertrand Russell: Advocated for logical atomism and the analysis of definite descriptions.

- Ludwig Wittgenstein: In his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, argued that the structure of language mirrors the structure of reality. Later, in Philosophical Investigations, he emphasized ordinary language and language games.

- Willard Van Orman Quine: Challenged the analytic/synthetic distinction and contributed to philosophy of science.

Common Traits:

- Focus on small, well-defined problems

- Alignment with scientific method

- Avoidance of metaphysical speculation

- Heavy use of formal logic and argumentation

Analytic philosophy became dominant in Anglo-American universities, often associated with academic rigor and formal precision.

III. Continental Philosophy: Experience, History, and Subjectivity

In contrast, continental philosophy is less concerned with logical formalism and more focused on historical context, lived experience, subjectivity, and power structures.

Key Movements:

- Phenomenology: Edmund Husserl’s method of examining consciousness from the first-person perspective.

- Existentialism: Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus focused on human freedom, angst, and authenticity.

- Hermeneutics: Hans-Georg Gadamer emphasized interpretation and historical situatedness.

- Critical Theory: The Frankfurt School (Adorno, Horkheimer) critiqued capitalism, culture, and modernity.

- Post-Structuralism: Foucault and Derrida questioned objective truth, language, and identity.

Common Traits:

- Use of narrative, metaphor, and literary techniques

- Rejection of the idea of objective, context-free knowledge

- Emphasis on phenomenological and cultural insights

- Interest in power, ethics, and social critique

Continental philosophy, though more popular in Europe, had a strong cultural influence in art, literature, and political theory globally.

IV. The Methodological Rift: Logic vs Meaning

At the heart of the analytic vs continental philosophy split is a methodological rift:

- Analytic: Truth is verified through logic, evidence, and precision.

- Continental: Truth is interpreted through context, history, and lived experience.

An analytic philosopher might ask, “What is the logical structure of moral language?” A continental philosopher might ask, “What are the existential conditions of moral responsibility?”

This difference made mutual intelligibility difficult. Where one side saw clarity, the other saw reductionism; where one saw depth, the other saw vagueness.

V. The Politics of the Divide

The divide wasn’t just intellectual—it was institutional. Analytic philosophers often held more sway in English-speaking universities and viewed their approach as more “scientific” and academically respectable. Continental thinkers, in turn, were accused of obscurantism or even nihilism.

Books were published in different presses, journals catered to different audiences, and philosophers were trained in separate canons. Some graduate students were told never to cite a continental philosopher in an analytic department—and vice versa.

This cold war within philosophy shaped the 20th-century intellectual landscape in profound ways.

VI. Bridging the Gap: Is the Split Fading?

In the 21st century, there’s increasing dialogue between the camps:

- Neo-pragmatists like Richard Rorty embraced ideas from both sides.

- Phenomenology of mind is now discussed even by some analytic philosophers.

- Philosophy of language, once the analytic stronghold, is increasingly informed by hermeneutics.

- Courses and anthologies often include thinkers from both traditions.

Yet differences remain. The analytic vs continental philosophy split reflects deep contrasts in worldview—between explanation and interpretation, between structure and fluidity.

VII. Why the Split Still Matters

Understanding the analytic vs continental philosophy divide is essential not only for philosophy students but for anyone curious about the intellectual undercurrents of our age.

- In law, psychology, and education, analytic clarity may reign.

- In literature, ethics, and critical theory, continental nuance is prized.

The real insight is that these traditions are complementary, not contradictory. Truth may demand both logical analysis and existential meaning, both empirical verification and cultural understanding.

VIII. Conclusion: Toward a Philosophy of Wholeness

The split between analytic vs continental philosophy marked an era of specialization, divergence, and sometimes misunderstanding. Yet today, as disciplines integrate and challenges grow ever more complex, a synthetic approach gains appeal.

Philosophy thrives not by building walls but by opening dialogues. If we can learn to speak across traditions, we may recover philosophy’s original mission: to think deeply and clearly about the world and our place in it.